Research, statistics, and numbers alone don’t create a good standard sizing chart for garment designers. It is those numbers and that work, together with empathy, spatial perception, and years of observing bodies and understanding fit that contribute to inclusive sizing. What follows is a deeper dive into those invisible aspects of my research.

Most of us can’t make or buy a piece of clothing that fits well without making modifications to it, and no single size chart alone will resolve that. It’s unrealistic to assume that we can make a sweater that fits us well by choosing one size based on the circumference of one part of our body. Bodies are diverse.

My goal is to be inclusive of as many bodies as possible while understanding the limitations of a single sizing tool.

Many proportions in existing standard body size charts are not consistent with what I see in my students, clients, and bodies I’ve measured myself. My goal is to improve the standards designers are working with, while simultaneously teaching makers how to resolve the more common fit issues and working with individuals to address specific fit challenges.

It is this combination of research, cultivation of understanding, and education that contributes to better fit.

Focus on Issues with Circumferences

The primary way I can address fit in a sizing chart is by focusing on body circumferences. Lengths are more challenging due to the broad variation of length proportions. If five people of the same height have the same upper torso, full chest, waist, and hip circumferences, the measurement of length from armpit to waist is more likely to be different than the same. While lengths are often easier to modify than circumferences, given the choice of making circumferences or lengths in body size charts more consistent with actual bodies, I believe circumferences are more useful.Height Matters

Height greatly affects the proportions of our clothing. At 4’11.5″/151.13 cm tall, I must adjust length proportions in all garments I make for myself, even when I design using my own size chart. When you are very short or very tall, fit issues related to height affect anyone who falls outside of the “regular” height category as determined by the fashion industry. Many people find that design elements like pockets and collars need to be scaled up or down to feel in balance with their body.

Petite, Regular, and Tall are terms that are often misunderstood. They are used to describe stature alone, and not related to circumferences at all. You can be anywhere from size 0 to 30W and still be Petite, Tall, or Regular.

- Petite: under 5’3″/160 cm

- Regular: 5’5″ to 5’7″/165.1 to 170.18 cm

- Tall: 5’8″/172.72 cm or taller

For reference, the ideal model height for women’s clothing in the fashion industry is between 5’9″/175.26 cm and 6’0″/182.88 cm, which is solidly within the Tall category.

When we look at statistical information about height in North America, the numbers differ from fashion industry standards. My chart focuses on people with breasts, however I’m beholden to statistics that use gendered language, so to align my charts with theirs at this point in time I’m sharing their “average heights of women,” interpreted as “female assigned at birth.”

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- 5’3.5″/161.29 cm

World Population Review 2022

- Canada: 5’5″/164.73 cm

- US: 5’4″/163.61 cm

ASTM (American Society for Testing and Measurements)

- 5’5″/164.73 cm is the single height measurement used across its Misses and Women size charts.

Even across these sources of statistics, “average height” for persons assigned female at birth is at the low end or lower than what the fashion industry has dictated.

I believe this deeply affects those over 6’0″/182.88 cm and under 5’0″/152.4 cm in how clothing and patterns fit. Scale and proportion of design elements like hemlines and sleeve lengths, collars and pockets, along with their position on the garment, are more likely to be out of sync with bodies as they get further away from the fashion industry “average” height ranges. When it comes to shorter or taller bodies, we can make some assumptions about proportion. For example, Petite women are more likely to have shorter arms, and Tall women are more likely to have longer arms. Both may need pockets placed at a different level and may also need options for changing the size of the pockets—smaller or larger, respectively—to be more in proportion to their garments. Even within a sleeve length, Petite and Tall women can assume they will need to make modifications to better suit their proportions.

You Forgot About Disabled Bodies

Growing up, disabled bodies represented most of the people in my life. Until I was eight years old, I thought that having a disabled body was typical. My mother taught special education and often took me to class with her. Because everyone there used a mobility device, I assumed that when I got older, I would have one too, that it was a part of growing up. This idea was reinforced when my Mum broke her leg and was on crutches for a month. Because of these early experiences, disability was my normal—something that hasn’t really changed.

Then, when I was fifteen, my mum became a quadriplegic, giving me an intimate look into accessibility for wheelchair users. I remember Mum asking me if I was embarrassed because she used a wheelchair, which was a huge shock to me. She had raised me to understand that people are people and deserved equity, no matter their ability, gender, sexuality, age, culture, or colour. It was my first clue that this attitude was not typical. Mum was a lifelong maker, still able to knit, sew, and weave despite her loss of mobility. We often talked about clothing design and fit, and how that changed for her after her accident.

Because of my experiences as a child, with my mum, and later in jobs where I worked one on one with children at schools and activity centres, a wide range of disabled bodies are prominent in my thinking about sizing.

When I’m approached with questions about measurements and sizing for disabled bodies, my first question is this: Which disabled bodies? People with spina bifida, cerebral palsy, dwarfism, cancer, paraplegia, quadriplegia, diabetes, lymphedema, and cystic fibrosis are just a few examples of disabled bodies with different body dimensions, fit, and accommodation needs.

One standard size chart for all people with breasts cannot capture every variation for every disabled body, but it does allow us to understand what body dimensions are captured, so we have a better sense of how a pattern can be modified.

How we take measurements is also important. For example, if a person is a wheelchair user, their measurements should be taken while in the chair and then compared to a body size chart. The person may need a different size than if they were to stand or lay down to accommodate their disability. Body measurements should be taken in ways that make sense for you, your clothing, and your life.

Offering adaptive fit for bodies that have had mastectomies, scoliosis, or amputations; pockets for medical devices such as insulin pumps or colostomy bags; and accessibility options such as closures and alternative garment openings are examples of ways designers can make their designs more inclusive.

Having a body size chart as a reference can help in the design of garments across a range of sizes, but it cannot resolve accessibility or adaptive issues alone.

Interesting Quirks

While chest, hip, waist, and bicep measurements might differ from body to body by several centimetres/inches, the measurement that doesn’t vary greatly is wrist circumference. Most fall within a range of 15-18 cm/6-7 inches. I’ve rarely seen a woman’s wrist circumference that’s outside this range, and when I do it’s typically within a centimetre or half an inch. My size chart has a wider range that combines my findings with those of Craft Yarn Council and ASTM charts. Actual wrist circumference accuracy is not as essential as other measurements because cuffs require ease to fit over the hand. Knit/crochet fabrics will stretch, while woven garments require more ease to fit properly.

If you find your clothing is tight across your upper back, you may wonder why Cross Back measurements aren’t included in my chart. I use Cross Chest instead of Cross Back for a number of reasons. Shoulder fit is important, and the Cross Chest measurement is key to achieving good fit in the shoulders. When a sweater fits well in the shoulders, it feels better and gives the impression that the whole sweater fits. I find Cross Chest a much more useful measurement, not only for getting excellent fit in the shoulders, but for neckline and cardigan opening widths as well.

The Cross Back measurement doesn’t vary person-to-person as much as Cross Chest does. Differences between an individuals’ Cross Chest and Cross Back measurements are rarely outside of the range of ease that’s inherent in hand-knit or crocheted fabric. When there is a difference of more than 7 cm/2.5 inches between the two measurements, there are simple modifications that can be used to account for the difference, ranging from choosing the average between the two as your “Cross Chest” size, to adding short rows in the upper back of the sweater to minimize the tension in the fabric.

In building a size chart, patterns develop with fairly predictable relationships between the numbers as bodies change size. Finding outlier measurements like wrist circumference and Cross Back defies those patterns. Remember that while the numbers in a size chart represent averages and proportions, there are always those of us who fall outside them. You are important. You are why I continue to explore fit, our differences, and how to modify clothing for bodies that fall outside typical ranges.

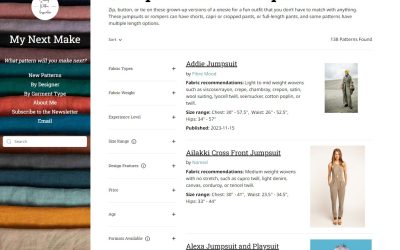

Remember Why This Exists

Sizing standards exist to give designers and clothing manufacturers a consistent guide for sizing their clothing. For garment designers, having a size chart to work with allows them to build patterns for a set of sizes based on a limited set of numbers. It is a tool that allows us to have patterns. However, we must remember that the dream—that a pattern should be able to fit a wide range of bodies perfectly, when most of us differ from the “standard”—is unrealistic. We can create standards that get us closer to the ideal, but a perfect fit with one pattern for every body cannot happen without modifications. Therefore, understanding where the pattern starts from, and how it compares to our own bodies, is the first step in learning how to work with a pattern to get a garment that fits you well.