Warm mittens are a necessity for Canadian winters. From the damp cold of the maritime provinces to the deep-freeze of the northern territories, keeping hands comfortable is a constant seasonal battle for us all.

My father hails from Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. He and my grandfather enjoyed subsistence offshore fishing and spent many winter days in their fishing boat despite the frigid conditions of the North Atlantic and Lunenburg fishing mittens were an essential part of their gear. My father, Eric, still has several pairs that he continues to subject to heavy use.

Traditional Lunenburg fishing mittens were handknit from handspun yarn. They were made oversized to allow for shrinkage and felting, which was achieved by soaking the mittens in salt water and heating them on the exhaust manifold of a boat engine. The heat combined with the lanolin in the yarn encouraged the fibres to mat together so that the mittens became thick, durable, and windproof.

The fishing mittens worn by my father and grandfather were handknit by my grandmother using yarn handspun by my great-grandmother. Since Lunenburg superstition maintains that grey mittens are bad luck, the mittens were always made from white or dirty white yarn. My great-grandmother must have been a prolific spinner, since several skeins of her rough-but-durable yarn now reside in my stash, even though she’s been gone for over half a century.

I now live in my husband’s hometown of Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, and have become accustomed to winters where temperatures often reach -50 C with windchill. The dry northern cold is more tolerable than the bone-chilling damp cold of the east coast, so we enjoy outdoor winter activities, and I wondered whether Lunenburg fishing mittens would function well here.

Armed with my great-grandmother’s handspun yarn, my grandmother Hazel’s notes, and measurements from my father’s mittens, I decided to reconstruct a pair—with a northern twist. My plan was to reverse engineer the pattern, knit a replica pair from the inherited yarn, felt the mittens using the exhaust from my snowmobile, and test them for ice fishing.

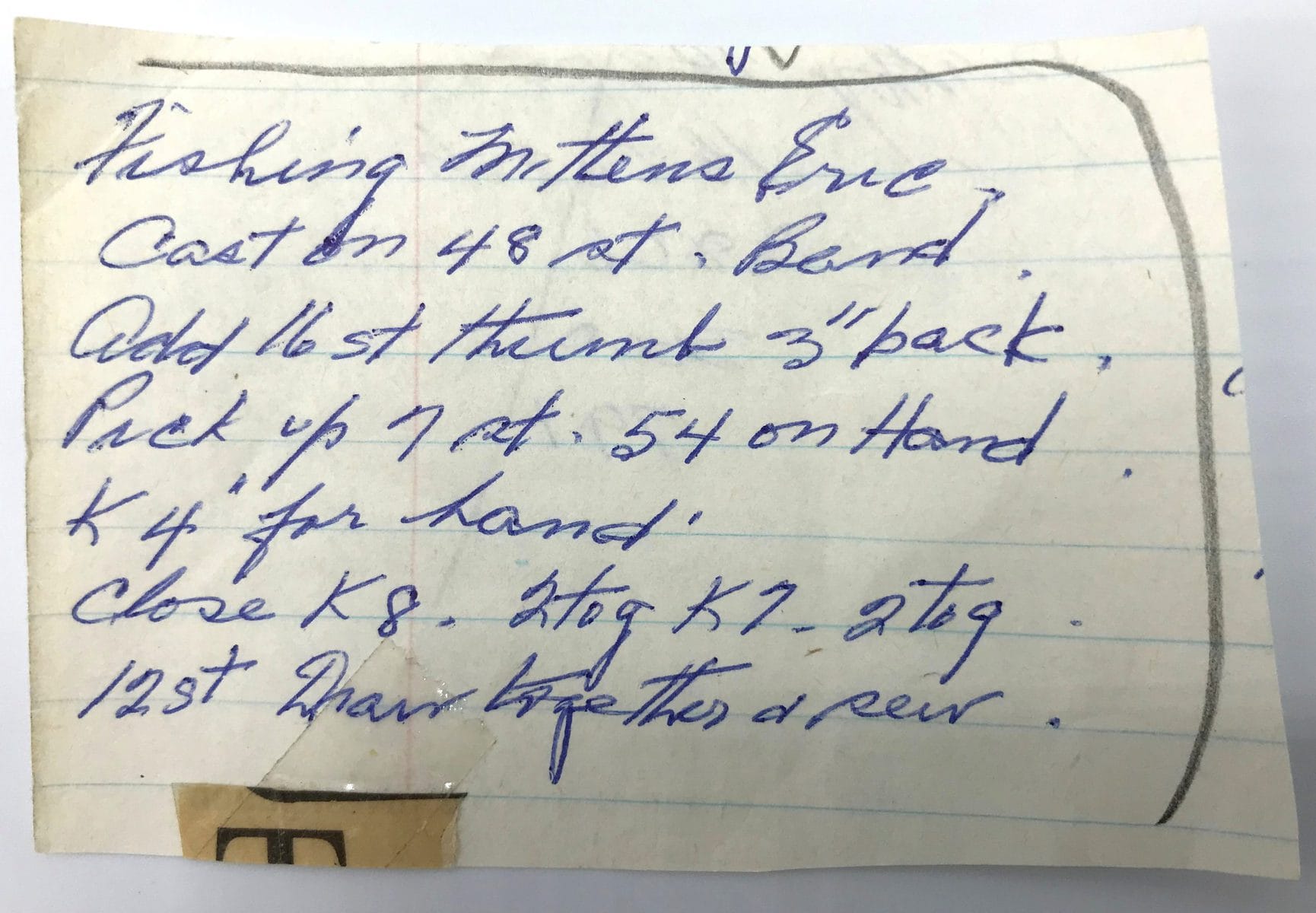

Cynthia’s grandmother’s notes.

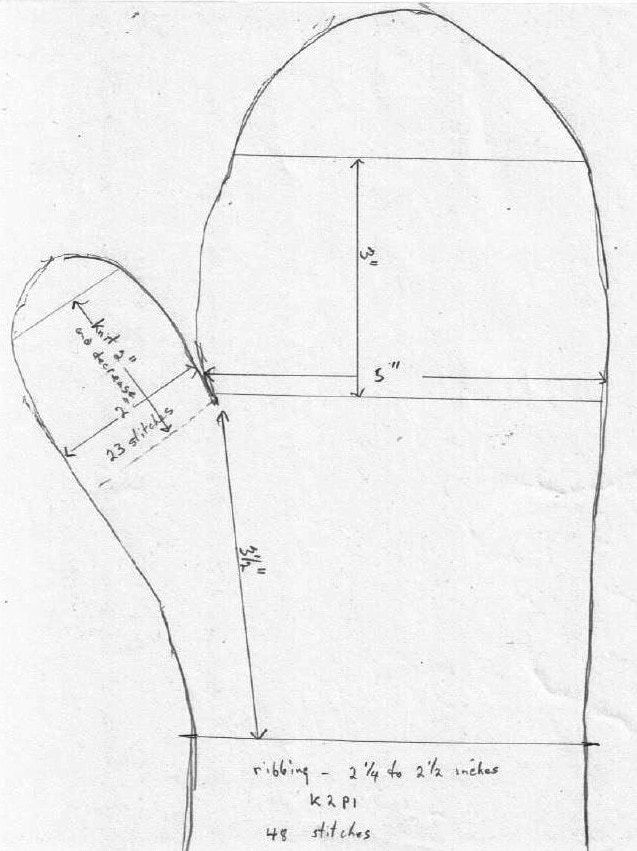

The original mitten’s measurements.

In addition to the remainder of my great-grandmother’s handspun stash, I’ve also inherited some of my grandmother’s handwritten notes containing her knitting formulas and other tidbits of wisdom on random topics. While browsing through them, I stumbled across the formula for “Fishing Mittens Eric” which obviously served as her pattern for making fishing mittens for my father. Her entire pattern is no larger than a business card and consists of just a few numbers and words, but it did provide me with a starting point.

My first step was to tap into my father’s memory and wheedle my mother into a careful examination of his fishing mittens. My father provided anecdotal information while my mother extracted measurements and stitch counts. We quickly realized that every mitten was different, and that the formula was merely a guideline. I decided to just start knitting but stay as true as possible to the stitch counts and measurements derived from the original mittens and my grandmother’s formula.

I guessed the needle size, remembering that my grandmother had many UK size 9 and 10 needles. I chose my favorite double-points and was lucky to achieve appropriate gauge on my first try. The cuff ribbing was easy and proceeded quickly.

The thumb gusset in the original mittens started immediately above the ribbing. Although my grandmother only used knit-into-front-and-back increases, I took the liberty of replacing them with make-one increases to provide a smoother look. My grandmother was always keen on modernization so she would have approved of the change.

The decreases for the top of the hand were simple, but revealed mathematical errors in my grandmother’s formula, so I had to calculate my own decreases. Her formula omitted instructions for the thumb, but my mother’s measurements and stitch counts proved helpful.

My replica mittens turned out surprisingly well. They were certainly large but looked and fit like fishing mittens. The real test would be in the felting process.

Ready for felting.

Fishing mittens were traditionally felted by soaking the mittens in salt water and then heating them on the exhaust manifold of a boat engine. Being in Yellowknife rather than Nova Scotia, I decided to try felting my replica mittens by dipping them in a freshwater fishing hole and toasting them on the exhaust pipe of my snowmobile.

After waiting for the temperature to rise above -25 C, my husband and I set off on our snowmobiles for an afternoon of ice-fishing on Great Slave Lake. We set up our tent and drilled some holes, and I eventually summoned up enough nerve to dip the mittens into the icy water and swish them around until they became thoroughly soggy. The instant enlargement of the mittens was shocking. My deliberately over-sized mittens instantaneously grew several sizes!

Since the snowmobiles had become as cold as the wet mittens, my husband drove one around to warm up its engine, and then opened its cowl to access the exhaust pipe. He reluctantly placed his hands in the soggy mittens and rested them on the hot exhaust. We then realized that the exhaust pipe doesn’t get particularly hot at sub-zero temperatures—its sides were barely warm. The top, however, produced enough steam to start the felting process and made the mittens a little fuzzy and rather dirty.

Creative solution #1.

Creative solution #2.

This experiment has given me a deep appreciation for the materials and labour involved in making Lunenburg fishing mittens. The yarn has already proven its durability through age and abuse, and the mittens will probably continue to improve over time. Four generations had a hand in making my mittens: My great-grandmother spun the yarn, my grandmother provided clues to the pattern, my father supplied information and memories, and I managed to improvise enough to create a pair of Yellowknife fishing mittens. I think they’ll serve well on my next ice fishing expedition.

Ready for the next ice fishing expedition.

All images credit Cynthia Levy